Sold in hospital shops and promoted by physician endorsements, cigarettes were once ubiquitous on U-M’s medical campus

Authors |

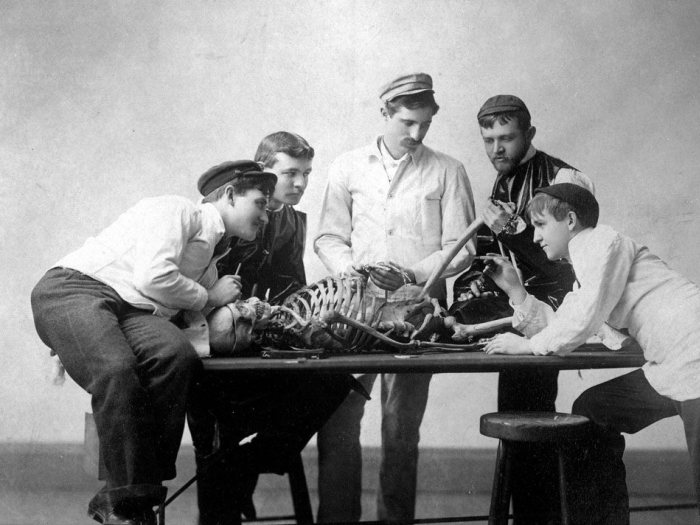

In 1914, a group of the best University of Michigan medical students — the tops of the class — formed a new society to mediate issues between students and faculty. They named the group the Galens Medical Society, after a legendary Greek physician.

The society then created an operating committee, to better organize themselves. Their first item of business: to get a dedicated smoking room for the students. While this choice of priority might seem surprising today, cigarette-smoking was widely seen as normal in 1915. In the following decades the advertising industry began to aggressively push cigarettes, and physicians became spokesmen for the tobacco industry. It seemed entirely reasonable, then, for these students to seek the availability of a safe and private place to smoke.

While there were some regulations about who could smoke in the medical buildings — and where — the concern was not over health but over safety. For example, in the 1930s, the Medical School dean called for renewed attention to the rules about smoking. His reason? There had been 20 fires over the past two years, of which seven had been due to smoking. He called for students and faculty to use care and to follow the rules — not to protect their health, but so as not to burn down the building.

Smoking continued to be ubiquitous in American society in the years after World War II, and cigarettes were valued commodities both outside and inside the hospital. Some public spaces started to ban or restrict smoking, but hospitals continued generally to allow it. Any discussions about whether to restrict smoking in hospitals revolved around the dangers of fire.

It was not remarkable to see physicians making rounds on the hospital wards with an ashtray on the chart rack and cigarettes in their mouths.

That concern, however, wasn't enough to keep smoking out of hospitals. A few decades after their formation, the Galens Society created a hospital shop whose profits were dedicated to children's programming at the hospital. Through the 1950s and 1960s, the Galen stand sold books, magazines, cookies — and cigarettes. Staff and visitors could conveniently buy their daily ration and know that they were helping children. Volunteers took carts around for the patients not physically able to make it to the hospital shop, so they could purchase the essentials, including cigarettes.

In 1964, the U.S. surgeon general issued a report detailing the health hazards of smoking. Although this report was not immediately followed by restrictions within hospitals, some people began to wonder if it was appropriate for these institutions to sell cigarettes. In 1969, the Galens Society asked that cigarette sales be banned at University Hospital. The Medical Center director was concerned about the implications of such a ban, however, and wondered whether it would prompt staff to undertake "smuggling practices reminiscent of the Prohibition Era." He was likewise concerned that it may cause "undue interference with patient prerogatives." In 1970, the Galens Society decided to stop selling cigarettes at their shop, even though the loss of profits would reduce the funds they were able to dedicate to the hospital's children.

Visitors, staff and patients continued to smoke. Staff members connected their need to smoke with the stress of the work environment. A study at University Hospital in 1982 found that nurses who smoked found their job more stressful. The highest rates of smoking were among psychiatric nurses and the lowest among pediatrics nurses. Still, it seemed "normal" to smoke. It was not remarkable to see physicians making rounds on the hospital wards with an ashtray on the chart rack and cigarettes in their mouths.

Physician groups lagged in making connections between increasing awareness of the health hazards of smoking and the professional environment. Medical society meetings often featured a not-so-subtle tobacco haze through which attendees would view the slides. The AMA Council on Scientific Affairs suggested in 1984 that physicians should take the lead to try to reduce smoking in hospitals. They pointed out that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization, or JCAHO, requirements still regarded smoking as more related to fire safety than health. This was no minor problem: As new technology enabled widespread use of oxygen in patient's rooms, the dangers of an ill-advised flame could be (and too often were) catastrophic.

In 1992, the commission decided that if hospitals wanted accreditation they must go smoke free. This decision was not without controversy. Some insisted that it was absurd to insist that some classes of patients — especially those with terminal illnesses — be forced to stop smoking at times of extreme personal stress simply because they were in the hospital. As a result, the Joint Commission standards allowed hospitals to make exceptions for certain patients.

Physician groups lagged in making connections between increasing awareness of the health hazards of smoking and the professional environment.

One group of patients at U-M who were exempted was the adult inpatient psychiatric unit, 9C. The unit had a smoking room dedicated to patients (and used by staff) until the year 2000, out of the recognition that the rates of smoking among the mentally ill are substantially higher than the general population. In line with common arguments until fairly recently, it seemed inhumane to deprive psychiatric patients, who were often hospitalized against their will on a locked unit, of the emotional crutch of their cigarettes.

Not so long ago, medical students had dedicated smoking rooms and volunteers sold cigarettes door-to-door within the hospital. The Galens Medical Society still thrives as a philanthropic entity, but they raise money without cigarettes. Today, smoking is banned not only within the hospitals, but anywhere near them.

Hirshbein (M.D. 1997) is a clinical professor of psychiatry. Howell, the Victor C. Vaughan Professor of the History of Medicine, holds appointments in the Medical School, the School of Public Health, and the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.